Los Angeles is home to almost two dozen low-power FM community radio stations. Venice’s KTPC 99.1 might be the wackiest of them all.

Somewhere in Venice stands an 80-foot-tall antenna broadcasting jungle music. Its signal regularly battles for airwaves with the Inland Empire’s Hottest Hit Music, the 2550-watt, iHeartRadio-owned KGGI. But drive within three miles of this Venice antenna, and the interference starts to fade. You’ll hear it — a toilet flush, a surf guitar riff, a space-ray beam, a bong rip. Then, a Brit speaking the Queen’s English tells you you’ve arrived: “You are now listening to 99.1 Venice FM, community radio.”

That’s it. Back to the music on KTPC, now playing Russian turbo polka metal.

KTPC 99.1 arrived in Venice in December 2018, when the antenna went up. The music is weird and experimental and counterculture, much like Venice, or Venice once upon a time. Now, the beachside neighborhood is where the wealthy and the homeless live next door to each other, where you can’t tell if someone is talking on his AirPods or to the voices in his head. But the dial’s not dead on Venice yet, and this homegrown radio station might be among the antidotes it needs to face the Westside’s growing pains.

KTPC was started last year thanks to a new wave of low-power FM (LPFM) licenses granted by the Federal Communications Commission to serve cities and their niche and underserved communities. Initially reserved for rural areas and churches back when the FCC issued the first surge of licenses in 2000, LPFM stations expanded to urban markets after the Local Community Radio Act was signed into law in 2011.

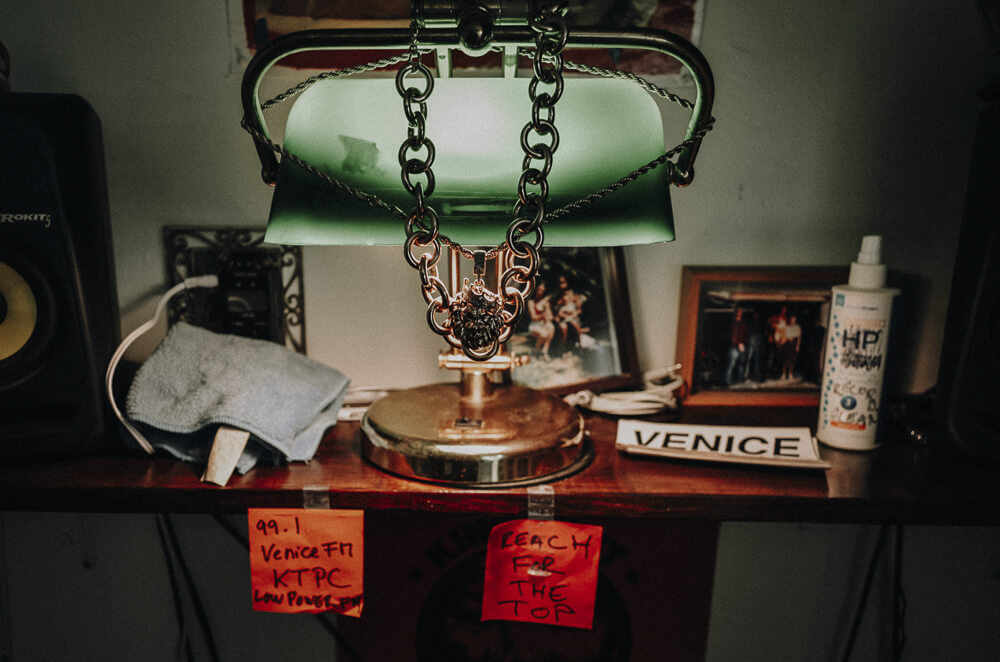

Tony Mackenzie’s Venice bungalow doubles as a radio station. From here, the 30-year Venice resident manages the music and shows that air on KTPC. Photo by Alexander Hayes.

According to FCC guidelines, LPFMs must be noncommercial operations, and can generally count on 3.5 miles of radio signal. There are currently 2,178 LPFM stations in the country, with 17 in the Southland, spanning from the San Fernando Valley to Long Beach, Anaheim, Santa Ana and out toward Newport Beach and Laguna Niguel.

“It took the FCC almost 14 years to create a service that could exist in Venice,” says Clay Leander, a consultant who helped KTPC and other groups in L.A. apply for licenses. “Who knows when the FCC is going to open the next window. These licenses are a rare resource.”

Venice has Ivonne Guzman to credit for fighting and winning the last round of LPFM submissions in 2013 — widely considered the last public grab at FM radio space. It took five years — from organizing and filing to securing and building — for Guzman to bring radio to her hometown through her organization, Reach for the Top, Inc., which helps the homeless in Los Angeles find permanent housing.

Tony Mackenzie is the not-so-posh Brit behind the station’s absurd jingles and music programming. He reckons the station has cycled through 40 to 50 radio hosts since launching, with hosts who either live in Venice or have lived there but were priced out of the community. He doesn’t want to mention the G-word, though (rhymes with schmentrification). That stuff’s all been said before and will be said again. No, KTPC is dedicated to letting the artists lead the discussion around their community for a change.

“I used to have a community of friends around here, but now it’s gotten to the point where no one’s around,” he says in his cockney accent. “But now I have the radio thing and am getting something going again.”

Sitting on a bench near the corner of Rose Avenue and Lincoln Boulevard, Mackenzie knows about half of the people walking by, some of whom still need to get their shows to him. If you know Mackenzie, a man-about-Venice and local of 30 years, you’ve had a radio show on Venice 99.1 FM.

“You wanna make one?” he asks me.

If I did make a radio show, I would never know what time it aired or who listened. Without a schedule, archive or live-stream, the music goes only as far as it can be heard.

It’s all very DIY, Mackenzie admits. But he likes it that way, raw and real and littered with mistakes. It’s why he gave a friend, a homeless man, a tape recorder and dubbed him the “Roaming Reporter.” It’s why the music isn’t easy listening (think “Morning Becomes Eclectic” on acid). It’s in-your-face background noise. It’s complicated. Turn the dial at any moment and you could hear monkeys fight each other to the beat, rising to a crescendo of U.K. grime and transitioning into a Graham Nash tune.

Listeners are in for an auditory adventure when tuning in to KTPC. Mackenzie is known to ask friends to develop and host their own radio shows, which he then assembles into a 10-hour playlist that hits the airwaves soon after. Photos by Alexander Hayes.

“For me, there are two rules: no curse words and don’t get too abstract,” says James William Sinclair, host of the “Moon Musick Radio Hour” on KTPC. Instead of following a theme, he follows a song and sees where it takes him, even if it sounds like he’s just hitting shuffle.

“I like it better when I play Rod Stewart, then a punk tune, then some Vincent Gallo, then computer music,” he says. Recently, for the first time in a year, he started thinking about his listeners: who they were, what they were thinking. So, he included his email address on last week’s recording.

“I don’t even know if anybody’s listening to this,” Sinclair said. “This is just going out to the void. Music’s like that, though. Sometimes you never hear back.”

Standing on the shoulders of the infamous U.K. pirate radio stations, KTPC’s cachet remains in the underground and anonymous. There are no bus advertisements, no social media campaigns, no sparkling-new $21.7-million headquarters. It’s Venice’s little secret, broadcasting out of a leaky shed.

“For me, there are two rules: no curse words and don’t get too abstract.”

James William Sinclair, host of the “Moon Musick Radio Hour” on KTPC

No one except Guzman, Mackenzie and a few key players know where the KTPC antenna is located. Instead, most interact with the radio station at Mackenzie’s home studio. Among the McMansions and residential construction, his bungalow is a like piece of preserved old-school Venice. It’s what life would look like if you bought property in the then-slum by the sea, dumped a jacuzzi and bar on your front yard and let the neighborhood cocoon itself inside. He regularly invites radio hosts over to listen to vinyl and record shows on his Tascam recorder. When he has enough shows, he’ll upload them onto a 10-hour iTunes playlist and plug it into the transmitter, which goes into the antenna, which goes out to Venice.

After stopping by Mackenzie’s, I went home to start writing this article. I made a playlist for background music to write to (i.e., procrastinate). I was searching for lengthy instrumentals to sustain uninterrupted typing and encourage concentration. I started with some Chet Baker and followed that thread: more jazz, a film score, some sample beats, the “Game of Thrones” theme.

I was starting to think like a DJ, contemplating the order and obsessing over the flow of the playlist. Then, I remembered Tony’s invitation to make a show. I sent him the hour-long writing playlist to put on KTPC. Then, I filed my story. When I read the completed draft, I could hear the playlist all over again in my head.

I don’t know when it will air, or if anyone will listen — but it’s out there, somewhere between bong rips and toilet flush jingles.