The history of Griffith Park is a tale of coerced contracts, cursed land, paranoid mining barons — and ostriches? Join us as we peel back the layers of the park’s convoluted beginnings.

Countless myths and legends have sprung up surrounding Griffith Park since it opened in 1896 — some sweet, others sordid. It’s where Walt Disney allegedly dreamed up Disneyland while sitting on a bench watching his kids on the merry-go-gound. It’s home to a “wishing tree,” where people leave entries in a collective journal, and hidden gardens intrepid hikers might stumble onto. It was the site of California’s first “Gay-In” in 1968, its first Gay Rodeo in 1985 and, for some time, it was a notorious spot known for anonymous sex and satanic cult activity. It’s also haunted by ghosts, and more than a handful of bodies have been found hidden in the chaparral-covered slopes over the years.

“Discovering Griffith Park,” a new book by Modern Hiker’s Casey Schreiner, details the 70-mile-long network of hiking trails and sights around the park, which include Griffith Observatory, the Greek Theatre, the L.A. Zoo, the Autry Museum of the American West, the railway-themed Travel Town Museum and, of course, the iconic Hollywood sign.

A lot has taken place at Griffith Park in these last 124 years, but its legacy reaches further back and involves a dubious curse and whole bunch of ostriches.

RANCHO LOS FELIZ

The story begins with José Vicente Féliz, a Spanish soldier who accompanied Juan Bautista de Anza on his 1775 expedition to the area. Féliz looked over the first residents of El Pueblo de la Reina de Los Angeles, established along the Porciúncula River — now known as the Los Angeles River. He later served as its comisionado, essentially mayor and judge, on behalf of Alta California. In the late 1790s, he was given a 6,647-acre land grant on the outskirts of the pueblo, which came to be known as Rancho Los Féliz, and stretched across what is now Griffith Park, Silver Lake, Los Feliz and then some.

The Rancho prospered as it passed through the hands of several family members, eventually becoming the property of Don Antonio Féliz, who resided there with his sister, Soledad, and his niece, Dona Petranilla. In 1863, the land was either wrested by or passed on to a leading politician named Antonio Coronel by the ailing Don Antonio, who was dying of smallpox. Here’s where the story gets a little lost in folklore, and the infamous curse is laid.

Legend suggests — perpetuated by frontier writer Horace Bell — that Coronel and his lawyer, Don Innocente, drew up a will giving Coronel the land and attached a stick to the back of Féliz’s head to make him nod in agreement. Soledad would get some furniture and Petranilla got nothing. It does sound suspicious, doesn’t it?

And here is the curse, laid by Petranilla, according to Bell’s 1930 book “On the Old West Coast: Further Reminiscences of a Ranger”:

“Your falsity shall be your ruin! The substance of the Féliz family shall be your curse! The lawyer that assisted you in your infamy, and the judge, shall fall beneath the same curse! The one shall die an untimely death, the other in blood and violence! You, señor, shall know misery in your age and although you die rich, your substance shall go to vile persons! A blight shall fall upon the face of this terrestrial paradise, the cattle shall no longer fatten but sicken on its pastures, the fields shall no longer respond to the toil of the tiller, the grand oaks shall wither and die! The wrath of heaven and the vengeance of hell shall fall upon this place.”

Perhaps the curse is a myth, but the land sure changed ownership increasingly often over the next 30 years — between James Lick, Charles V. Howard, Elias Jackson “Lucky” Baldwin, Thomas Bell and Col. Griffith J. Griffith — until it was eventually given away. We’re going to skip over about 20 years of owners getting shot, cows dying, grasshoppers and fires destroying crops and a few other disasters, to when the park’s namesake bought the land in 1882.

Griffith made his way down to Los Angeles after finding success in mining investments. The 1880s were boom years for Los Angeles as the old ranchos were broken up into subdivisions. Griffith acquired 4,071 acres of the Rancho; the rest had already been parceled out. While he intended to maintain a working ranch, tourism and housing developments were the focus of his enterprise.

So when English naturalist Charles Sketchley proposed setting up an ostrich farm at the Rancho to attract visitors, Griffith saw dollar signs and jumped on the opportunity.

THE FIRST OSTRICH FARM

Sketchley brought a herd of ostriches to Southern California in 1883, establishing the first farm of its kind in Buena Park, near Anaheim, banking on the popularity of ostrich feathers in women’s boas and hats. It was a lucrative business, with a single feather fetching $3-$5. Moreover, people loved visiting the ostriches, these crazy-looking creatures from Africa. They liked watching them swallow whole oranges and seeing the bulge gliding down their long necks. People have always been and will continue to be easily amused.

Sketchley partnered with Griffith and moved his operations to Rancho Los Feliz in 1885, building a new farm on an oak-dotted ledge, which would later be the site of what we know as the Old Zoo. The zoo opened in 1912, post-Griffith’s ownership, and housed 15 animals before it closed in 1966 when the new zoo opened elsewhere in the park.

At the time, most of L.A. centered around the downtown area, and travel was slow. Going all the way to Rancho Los Feliz was a special outing. To capitalize on folks making a day of it, Griffith brought in exotic birds and animals like parakeets, monkeys, macaws, buzzard hawks, badgers, cockatoos, owls, wildcats, silver foxes and raccoons. There were picnic grounds and trails in the hills, a dance floor and a bar.

Griffith and Sketchley collaborated with other entrepreneurs to build the Ostrich Farm Railway through the unoccupied ravines and hills separating the Rancho from downtown Los Angeles. At the height of their popularity, they operated five trains a day back and forth. The route they laid out would eventually become the stretch of Sunset Boulevard that winds through Silver Lake and Echo Park. Then the ostrich farm concept really took off. By 1910, there were 10 ostrich farms around Southern California.

In 1889, Griffith and Sketchley closed up shop. Some sources cite financial difficulties — which is weird because Griffith certainly was rich. Some say the real estate boom tapered off. Others invoke the curse, ghosts haunting the land, ostriches stampeding for no reason in the middle of the night. It’s unclear. But what is certain is that the story takes another dark turn right about now.

WAS GRIFFITH A GOOD GUY OR A BAD GUY?

When Griffith decided to gift the land to Los Angeles as a Christmas gift in 1896, he insisted it had to be a park for everyone, not merely the rich. “It must be made a place of recreation and rest for the masses,” he told the City Council, “a resort for the rank and file, for the plain people.” This part seems super nice. Other accounts about his character are less favorable.

Apparently, he was a colonel of nothing, having given himself the title. His marriage to Mary Agnes Christina “Tina” Mesmer, the daughter of a prominent family, came on the condition that the massive inheritance meant to be shared between herself and her sister be given to Tina and placed under his name.

He was described as “a midget egomaniac, a roly-poly pompous little fellow.” Then he became an alcoholic, drinking two quarts of whiskey a day, paranoid that his Catholic wife — he was Protestant — was conspiring with the Pope to poison him. He would switch plates with her at meals just in case.

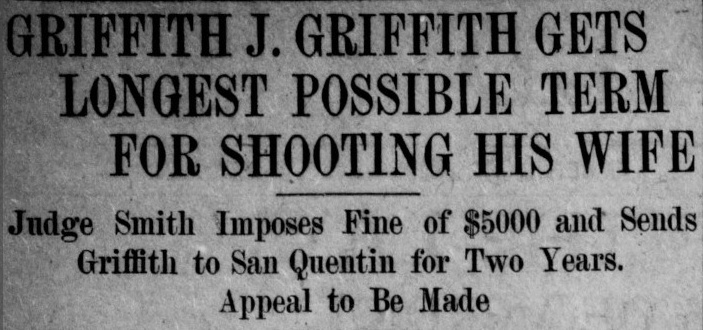

Griffith shot his wife in the face at Santa Monica’s Arcadia Hotel in 1903. She winced, which saved her life. She then jumped out the window and landed on a piazza roof below, where she was spotted by the hotel owners who pulled her to safety and called the cops. She wound up blind in one eye and horribly disfigured.

Griffith served two years at San Quentin, where he apparently behaved himself and did not seek any privilege above other inmates. Upon release, Griffith wanted to complete his dreams for Griffith Park, which included an observatory and an outdoor amphitheater, but the city wanted nothing to do with him — while he was alive at least. He created a trust that would eventually fund Griffith Observatory and the Greek Theatre. He died in 1919. The Greek opened 10 years later and the Observatory was completed in 1935.

You’ve likely driven by the statue of Griffith standing proudly in front of the park on Los Feliz Boulevard, so it would seem all is forgiven. Was it Petranilla’s curse, exacting its revenge that unraveled this generous but pompous man? Was it the whisky?

Perhaps some mysteries must remain mysteries.