The local artist explores the alchemy and power of the kitchen in her recent work.

For Los Angeles artist Alison Saar, the kitchen is more than just another room in the house. As she tells it, the kitchen is a space for creativity, alchemy and the empowerment of women. “The kitchen is this space of all these things happening, especially my family’s kitchen, African American kitchens,” she says. “Many kitchens of color are multipurpose spaces.”

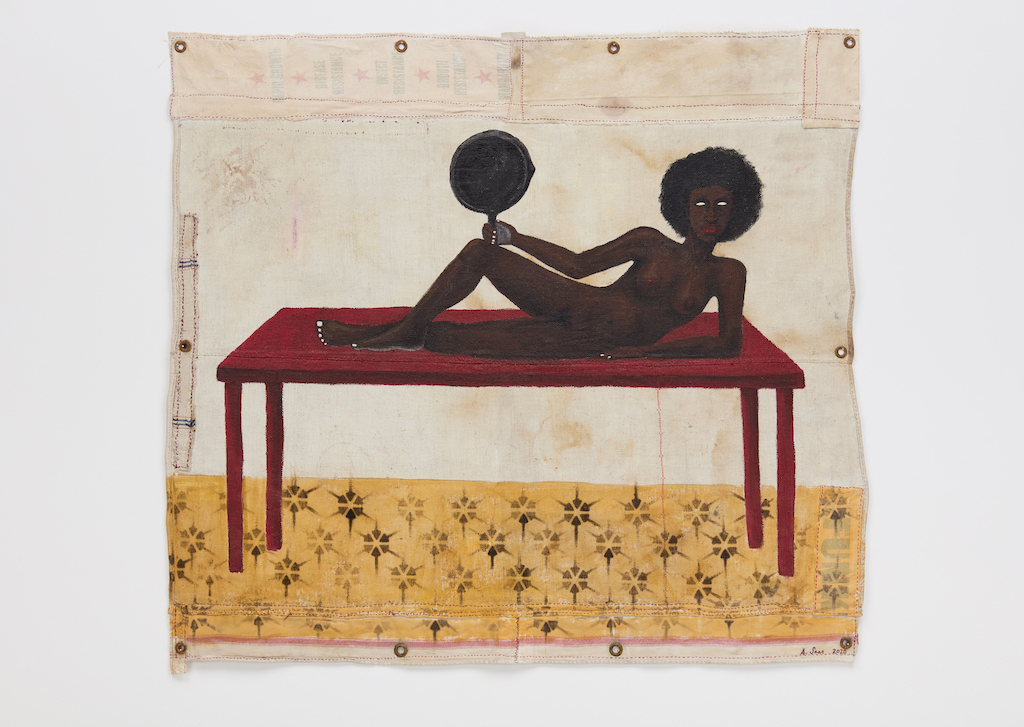

Saar explores the robust life of the kitchen in her booth at the Frieze Los Angeles Art Fair this weekend. Supporting her exhibit, titled “Chaos in the Kitchen,” is Venice-based gallery L.A. Louver. The collection comprises brand-new sculptures, paintings and assemblage work.

On the eve of the opening of “Syncopation” at L.A. Louver, Saar’s current solo show at the gallery pairing her prints with sculptures from across three decades, the artist took us on a tour of her Frieze presentation.

“That’s a giant one — 7 feet tall. We call her ‘The Big Singe,’” she says, pointing to an image of a new sculpture destined for Frieze. It resembles a blown-up hot comb, a metal comb used to straighten hair, the handle of which is a wooden sculpture of a nude woman painted in red.

“You heat them up on the stove, then try not to singe the hell out of yourself,” she says. “The handles are always burned at the end because they’ve been sitting on the stove.” To recreate this effect on the sculpture, she coated the end in spray tar.

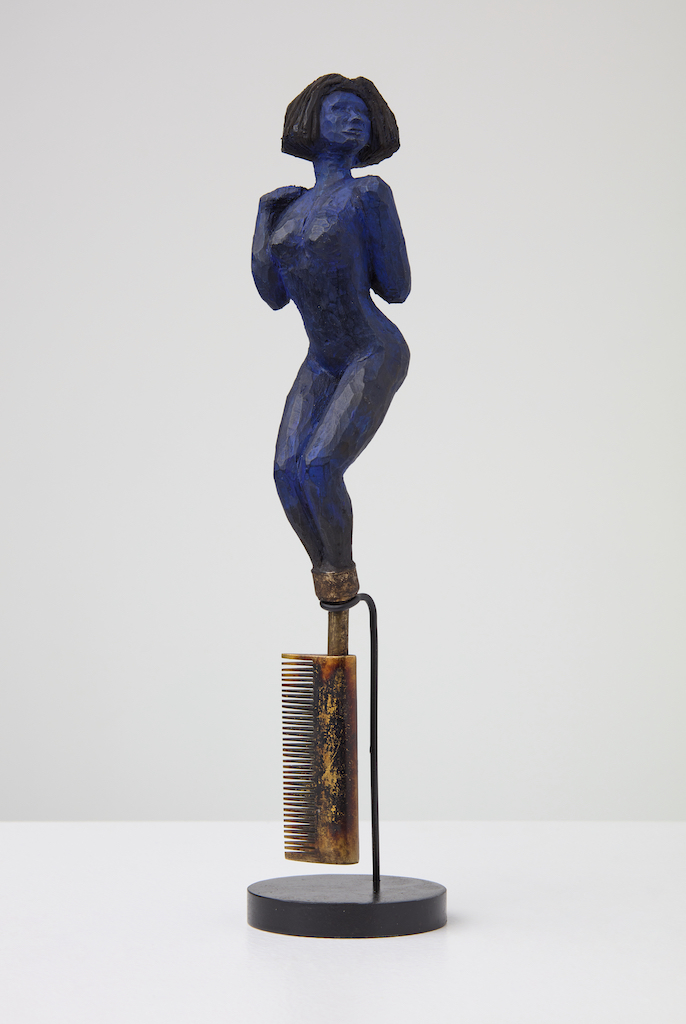

Smaller versions of the hot comb sculpture, titled “Hot Comb Haint,” reference the haint, a spirit from the Old South originating with the African American Gullah people on the Carolina coast.

“They’re female spirits that like to jump on you,” she says. “If you’re walking home, they’ll start following you home.” Southern homeowners often paint their porches a shade of blue called “haint blue,” intended to confuse and repel the mischievous apparitions.

“I became interested in creating these ‘spirits of hot combs,’ these wild spirits rebelling against Western beauty aesthetics,” she says, noting that the sculptures reflect her fascination with ceremonial tools made throughout Africa whose handles resemble figures.

Other works in “Chaos in the Kitchen” also reflect Saar’s interest in mining African, African American and American histories and imagery. Her 2019 sculpture “Kitchen Amazon” is an imposing figure made from nailed-together sheets of ceiling tin, a favorite material for Saar. Its pressed patterns form a decorative patchwork over the figure’s “skin.” A belt of cast-iron skillets hangs from a chain around her waist. In her left hand, she holds up another pan; ready to either defend herself or whip up a nourishing meal. She sports a fearsome afro of stiff wire.

Another sculpture, “Sorrow’s Kitchen,” strikes a more plaintive tone. Saar carved the solitary female figure from rough-hewn wood, which she painted a mournful, rich blue. She holds a pot with both hands, gazing into it as her reflection stares back. Her piece “Suckle Study” features a cast-iron pan out of which sprouts a breast, a surreal image evoking the nurturing aspect of cooking.

Overall, “Chaos in the Kitchen” is about defiance, emancipation and joy. “Congolene Resistance,” a small enamel painting on found tin, epitomizes these themes. Resembling the top of a hair pomade container, the work depicts the head of a wild-haired black woman, hot comb gripped between her teeth. The text on either side of her reads, “Stubborn and Kinky.”

To accompany the exhibition, Saar composed “Recipes for Trouble,” a small cookbook featuring dishes that reflect her family’s African American and Southern roots — greens, gumbo, cornbread, sweet potato pie and Hoppin’ John, or black-eyed peas. Each recipe has a musical pairing, with songs from Charles Mingus, Alice Coltrane, Booker T. and the M.G.’s and Nina Simone.

“This is about the importance of improvisation, it’s an opportunity sort of cooking,” she says. “But they all have other kinds of spiritual or superstitious components, dating back to coming overseas and slavery, so I was interested in that history. There’s all this mythology around those five recipes.”

Eating greens on New Year’s Day brings money, for instance, while black-eyed peas are for luck and yams for fertility.

This idea of the kitchen as a site of creation — culinary, social, artistic — dates back to Saar’s childhood. She grew up in Laurel Canyon, one of three daughters of Betye Saar, the seminal African American assemblage artist who, at the age of 93, still works and lives in the house she raised her daughters in.

“My mother used the kitchen as a studio and I often use my kitchen as a studio,” she says. “When I was a toddler, my mother was going to school as a printmaker. She got a press for the house and she would have acid baths for etchings in the kitchen.”

As visitors peruse the booths at Frieze Los Angeles or any of the handful of other art fairs touching down in L.A. this week, it can be easy to become overwhelmed by the sheer volume of art, often presented without thematic consistency or context. “Chaos in the Kitchen” offers a welcome alternative, inviting viewers into Saar’s exuberant hybrid melding of art and cuisine, history and liberation.

VISIT

Frieze Los Angeles takes place at Paramount Pictures Studio from Feb. 14-16.

5515 Melrose Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90038