The winners of ‘The Chicken Wars’ are clearly the chains themselves, but how have the employees on the frontlines fared as the popular dish readies for a return?

There have been car accidents, people jumping over counters, angry men banging on the windows, food being tossed through drive-thru windows, 90-minute line-ups, countless Uber Eats cancellations, weeks with no days off and phones that are still ringing and ringing and ringing. The question on the other end of the line is always the same: is that chicken sandwich back?

Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen employees have had a tough summer thanks to the most popular new fast food item in recent memory. Their crispy fried chicken sandwich was only available for a few weeks last month across its 3,000+ U.S. locations but that was enough time to seduce a salivating country — and L.A. was no exception.

The chain, which is actually based in Florida, had completely remade its previous incarnation of the chicken sandwich. The result caused The New Yorker to practically moan in ecstasy as they described the driving force behind the lines and the ringing phones.

The bun is “buttery and sweet and light,” the magazine says. The pickles are “sizable rounds of cucumber crisp with vinegar.” At its center is an “exquisite slab of chicken breast, heft and juicy and snow-white, in its crenelated armor of that uncommonly crisp fried batter.” Combined, the concoction “sticks the landing on the most important element of a fast-food sandwich: the fusion of its distinct components into an ineffable, irresistible gestalt. The salt, the fat, the sharpness, the softness — together, they’re what flavor scientists might describe as ‘high amplitude,’ a combination so intense, and so perfectly balanced, that they meld into one another to form a new, entirely coherent whole.”

This creation was perceived as a volley in what would be deemed The Chicken Sandwich War versus the Chick-fil-A sandwich. But a manager at the Georgia-based fast-food spot said she hadn’t noticed an uptick in sales at her Hollywood location either during Popeyes peak or once it had sold out. She said business was steady before and has remained busy since the “war” at the former Carls Jr. Jr. on the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Highland Avenue.

Hollywood

During the madness that began in the middle of August, Popeyes restaurants around L.A. felt the crunch.

Customers lined up an hour before the store opened at the Slauson Avenue and Crenshaw Boulevard location. Businesses were ordering a day in advance from the Hollywood Boulevard location. On La Brea Avenue, south of the 10, two endless rows of cars inched their way toward one drive-thru window while the lobby inside was packed despite the $4 sandwiches being sold out that night.

“It’s so tasty — and people weren’t ordering one. They were ordering 50, 100,” says Denny Morales, general manager of the Hollywood and Cahuenga Boulevards restaurant. “Office people would come in and they would order 100 at a time, and they would order a day before. We were thinking we would sell between 80 and 100 a day. We were selling between 800 and 1,000 a day.”

Morales said that to appease the long lines of hungry, but patient, customers she handed out licorice for the kids and cups of water.

The one person the affable manager couldn’t comfort was the psychic next door, irritated by the long line stretching out past her business.

“I told her she should have seen this coming. She should have given us a warning,” Morales says in her now more manageable lobby, which is still bustling, where the phone can be heard ringing as prospective customers ask when the item will return.

So why the delay? How can a chicken joint sell out of a chicken breast sandwich, when fried chicken breasts are right there under heat lamps stacked high and ready to be devoured? Did they run out of bread? Pickles? Hot sauce?

“The chicken fillets are boneless,” Morales says, differentiating the bone-in breasts currently available with the boneless ones for the sandwich. Also, they use a unique flour batter for this sandwich that they don’t use for any other product, as well as a special sauce that’s equal parts spicy and tangy.

“We could fake it,” she says, but neither the texture nor the taste would match what the nation is clamoring for. They would immediately spot the fried fraud.

To meet the insatiable demand, her store and others around L.A. asked their crews to work double shifts, managers worked 70-80 hour weeks and a few locations really felt the pressure when a handful of their employees chickened out and quit in the midst of the mayhem.

Just as quickly, though, right as the sandwich became a hit, the chain ran out. At first, hand-written sold-out signs appeared on front doors and drive-thrus. They are now replaced by corporate signage that dot the windows and overhead menus.

And yet, even without the 690-calorie wonder sales are up, in part by those who poke their head in to see if the sandwich has come back, who upon hearing the bad news order a few pieces of this and that as a consolation while they’re there.

“Now that it’s a lot less busy,” Morales says, “either we got extremely fast, or we adapted to that high traffic that now it feels so dead. And I look at the numbers and I say ‘guys, it’s not dead.'”

Western Avenue & Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard

Over two decades ago, Chris Rock had a joke about Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard: “If a friend calls you on the telephone and says they’re lost on Martin Luther King Boulevard and they want to know what they should do, the best response is ‘Run!’”

But if you go into the Popeyes on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, not far from USC, you’ll notice how large and clean it is. There are decorative spices and knickknacks in glass jars. Upbeat Dixieland brass band music booming through the hidden overhead speakers into the lobby. Lots of sun shining through the large, clean windows. Not at all the stereotype Rock described.

Sure, there’s a belligerent homeless woman yammering to herself, digging through the trash until she retrieves a few uneaten morsels of food, but that can be seen in most of L.A. When the store’s general manager, Elena Barrieiro, sternly tells her she’s not allowed to do that, the woman hisses at her and exits the restaurant with the leftovers.

Barrieiro has seen it all at this location, or so she thought, until that sandwich arrived.

Like most managers, she tasted the new creation before it was introduced to the public. She thought it was good, but she had no idea what it would do to her store, the employees, the customers and her life.

“When we tried the sandwich in training it was really good,” Barrieiro says, “but we didn’t expect it to go crazy.”

She says one reason for the delay of the return of the sandwich is so stores like hers can hire more crew members, train them properly, plan where they will house the extra racks of fresh buns and really prepare for the probable storm that will hit them again.

Unlike the Hollywood location, the King store lost some of its employees who just couldn’t handle the pressure. That added more stress to the remaining cooks and cashiers who worked doubles and collected overtime, but were beat from the lines that stretched around the block.

This is also the location where angry customers banged on the glass, threw trash through the drive-thru window, and where the car accidents occurred. While it’s great to be getting OT, that’s based on a minimum wage salary. Is it worth it?

Hector Amador, who grew up a few blocks from the Popeyes that he’s now a cashier at, says it was hectic, but exciting.

“I’d check my phone,” he says, “I’m supposed to leave at 5 o’clock. I’d check my phone, it’s 5:30. I be like, damn, I should have been home. Time goes by so fast.”

During the busiest weeks last month, Amador’s shift started at 4 p.m and ended at 2 a.m. This location is open until 4 a.m.

“You know the crazy thing about it? Four in the morning and there’d still be people trying to eat some chicken,” he says. “On a weeknight.”

His positive spirit was common among the staff and managers at various locations. Barrieiro worked 14 days straight, put in 12-hour days and had an hour commute each way to run a store where she regularly had to call the strip mall’s security and manage the difficulties of having the hottest hot chicken item in town. All of this while trying to juggle schedules, answering the phones (which are still ringing) and figuring out where to house 40 racks of buns as a lobby full of angry customers and impatient Postmates drivers stared her down.

“It was kinda hard,” she finally admits, but she quickly bounces back. “When you have to, you have to. I’m the store manager and that’s what we have to do. When you don’t have enough people, you have to do it yourself.”

Because she is on salary, she gets no overtime for her efforts but is hoping she will get a bonus - which is common for the franchise owners to bestow upon management.

While the Hollywood location hinted at mid- or late-October for the sandwich’s return, Barrieiro only says November. Perhaps some stores will get it early, she says.

And that’s when she says the most startling thing.

She heard that the restaurant on Slauson Avenue and Crenshaw Boulevard, just a few miles south, had acquired some of the elusive sandwiches. And they were selling them.

And like Chris Rock advised, this reporter ran from MLK Jr. Boulevard.

Slauson Avenue & Crenshaw Boulevard

There’s a lot to take in at the Popeyes on Slauson Avenue. The first thing you might notice as you approach it is that it’s located a block away from where rapper Nipsey Hustle was murdered in front of his shop, The Marathon Clothing. Another thing that greets you is a flat-screen TV on the north wall, which on Tuesday was airing Fox News. Not exactly what one would expect in a predominantly black neighborhood fried chicken joint.

The two general managers laughed when it was pointed out and explained that they often have the news or sports running on the TV and hadn’t thought about which network was on. They are far too busy to notice, and none of their customers complained.

Another thing you notice is here the phones aren’t ringing. Perhaps, in part, because it was true: the crispy chicken sandwich was there. And apparently off-menu, for the store’s best (and luckiest) regulars.

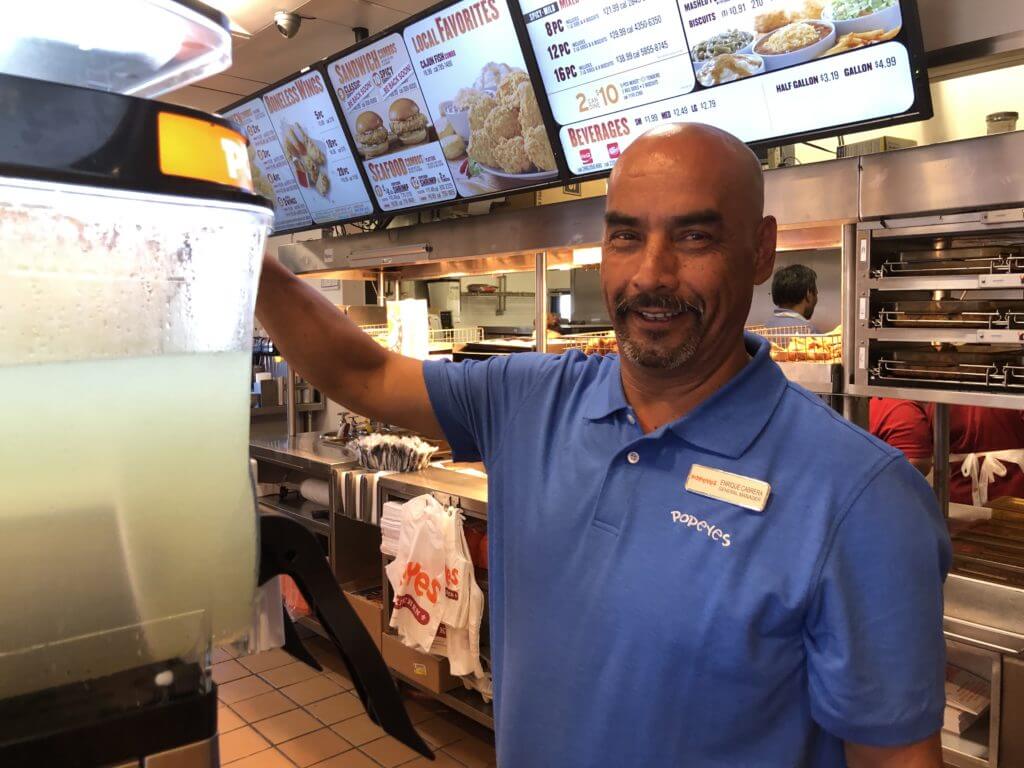

Enrique Cabrera has been running the place for 25 years. Some of his customers have grown up in front of his eyes and are now parents themselves. He boasts that he can easily spot new guests in an instant. The only time he says there was trouble at the store wasn’t during the sandwich frenzy, it was on the night that Hustle was slain. The anger and sadness over the tragic death of the neighborhood hero spilled into his lobby that night in March.

The emotional crowd struggled with their feelings and Cabrera and his co-General Manager Kulwinder Singh, struggled with removing those who had smuggled bottles of alcohol into the premises. Activity they say never happens there.

Cabrera, who proudly states the store has no problems with anyone, admitted that that night there was an air of disrespect that he’d never seen before. But it only lasted that night.

When it came to the chicken sandwich spike, however, the only flare-up Cabrera could recollect was one woman who got ticked off when she received too many pickles. Other than that, it was non-stop feeding of the masses.

“Man, you have no idea,” he says. “Big ol’ lines in the drive-thru and big ol’ lines in the lobby. The first week they were waiting about an hour and 30 minutes.”

But were they satisfied?

“They were so crazy about it. They enjoyed that sandwich and they’d come back. They’d keep coming back,” Cabrera says, smiling. “We open at 10 a.m. There was a line at 9 a.m. They just wanted to taste the sandwich. Once they taste the sandwich they want to come back for more. Most people don’t get one. They get 15, 18, four, five.”

Cabrera explains that Popeyes have had chicken sandwiches before, but he says it’s the spicy sauce that he thinks people are connecting with.

As Fox News yammered above our booth, the “$3.99 Question” arose.

The same question that Popeyes after Popeyes is asked via phone, squawk box and in-person.

Do you really have the sandwich?

Yes.

Yes?

Yes.

How?

“I was the one of the lucky ones,” Cabrera says. “I saw there was some product, so I ordered some. So they sent it to me.”

An accident?

“I think so,” he says.

Out of equal parts professional curiosity, due diligence and hunger, an order for the now almost-mythical meal was placed. Cabrera called out to his co-manager, who reached into the nearby cooler and emerged with the battered breast. As payment was made, the sandwich was prepared, and soon this reporter experienced the delight others had mentioned on social media and elsewhere. The generous slathering of spicy sauce was key. The bread was fresh.

The chicken was magically crispy and moist.

In this chicken sandwich war, one side has not yet begun to really fight.