‘Black folk are less than 10% of the population of L.A. and yet our culture and influence is everywhere.’

I’ve been black for a long time.

The first time I noticed I was different was when I was just a few years old.

I was in my stroller and I grabbed a candy bar from the corner market and tucked it under my blankie. It wasn’t until my mom had strolled me out of the elevator in our apartment building that she saw me working on the chocolate.

“What are you doing? What have you done?” she yelled, frantically. “Did you steal this? You stole this! You can not steal. We are black. We will all go to jail!”

She not only took me back to the market and paid for the candy bar (I think it cost a quarter), but she also made me apologize to the shop owner and swear that I would never do that again. Through tears, I apologized and, as it turns out, I’ve never stolen since.

Afterward, there were spankings delivered first by my mother and then later by my father. If my grandmother was around she would have beat my ass too. That’s how it was.

A funny thing happened when I got older: my skin got darker. And then years later, it got lighter. Today, it is so light that most white people think I’m Italian and many Spanish-speaking people speak Spanish to me.

But black folks know. In many black families, it’s not surprising to see a light-skinned cousin or two who “could pass.” That would be me. My sister, however, has the complexion of Oprah. Recessive genes are a thing. Yet when I pass a black man on the street, I will get a “whaddup brother” almost every time.

Being able to “pass” has its advantages when you are a journalist, especially when you have the accent of someone who grew up in an all-white Midwestern suburb.

But because I missed out on a lot of black culture out in the cul-de-sacs of Illinois, I moved to Inglewood a year after I came to L.A. This was the mid-’80s when crime was rampant thanks to a crack epidemic. It was also peak gang warfare in this beautiful city. It was so bad that black people just didn’t venture to places like East L.A. or other parts of town that were said to, let’s say, frown upon our people — allegedly.

It was a shame because black and brown cultures share more things in common than divide us.

So here we are now in 2020 and it’s Black History Month. I am 53. I don’t know when Black History Month became a thing, but I sure don’t remember it in high school or before.

Now when I hear it mentioned I don’t really pay much attention to it because how many times can I be told about MLK, Rosa Parks and George Washington Carver?

But I think the main reason it has lost its zing is due to one Barack Hussein Obama. See, back when I was one of the only minorities in school, I could have used a Black History Month. Even though I got along with the kids, the first girl I ever asked to be my girlfriend said no. “My dad would kick my ass,” she told me. And I understood exactly what she meant.

Clearly, her father did not want her giving birth to inventors who would create hundreds of different uses for peanuts.

Black History Month would have been important to me back then because it would have taught my classmates about the wide range of African Americans who either overcame some majorly messed up shit this country threw on them, or who prospered in freer parts of this nation.

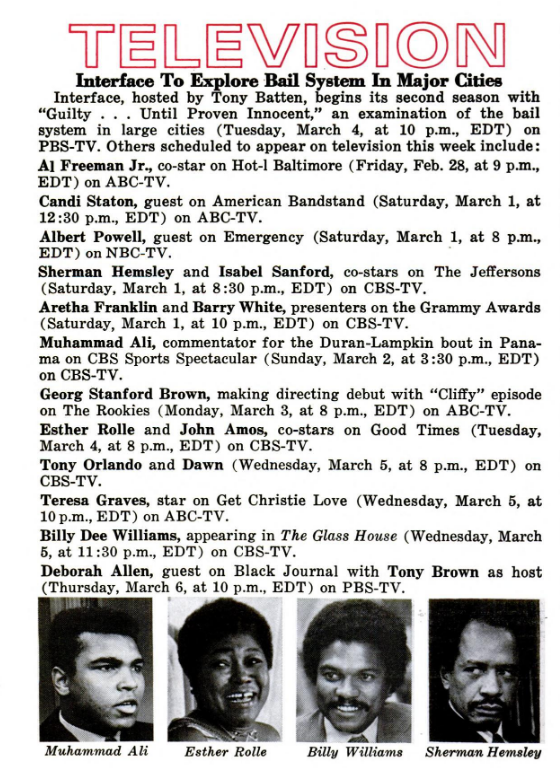

How else would they have learned? Television in the 1970s and early ’80s had so few black people that Jet magazine would list the handful who were scheduled to appear that week. It was always a short list, not just because Jet was a tiny magazine that you’d often find in the bathroom, but because even though we were some of the greatest entertainers in the world, there were very few shows that starred black folks. And the ones that did are now legendary.

Obviously things progressed, and then young Senator Obama ran for POTUS and won. And not only that, but he was all the things my mother and father and grandmother tried to beat into me: dress sharp, be smart, win them over with your intellect, marry a strong black woman, don’t do stupid shit, stay black — but be exactly whoever it is that is you.

You will have to work twice as hard and accomplish three times more than your counterparts to get the same accolades. Don’t whine about it. Don’t quit. But know it, do it and move on. One day it might change. But if it is going to change, you’re going to have to be the one who does it.

After Obama, I don’t feel like we have to prove to anyone anymore that black folks can do anything. He took a recession that had literally stopped development in places like downtown L.A. and Hollywood and turned it around. Millions of people went back to work and millions more had healthcare.

I grew up during a time when black people were considered too dumb to be NFL quarterbacks and here the first black president was running circles around his predecessor. And he was funny. And the world shared our love for him. And in particular, he was black and proud.

Our people had nothing more to prove. Not that we needed to before Obama, but the mic had officially dropped.

Black folks make up less than 10% of the population in L.A. and yet our culture and influence is everywhere. From all sorts of music to all sorts of athletes. People fly into Tom Bradley Terminal and have no idea who he is. They buy Fatburgers without realizing it’s been around longer than the clown and the king.

But to me, one of the more interesting developments that I have seen happen due to black culture is happening on Fairfax Boulevard.

When I first moved here in 1984, the portion of Fairfax between Beverly Boulevard and Melrose Avenue was almost all Jewish. It was a real East Coast throwback neighborhood with old people pushing granny carts stuffed with fresh bread past the deli. But even then, due to the proximity of the racially diverse Fairfax High, there were the beginnings of a few storefronts that didn’t quite fit in — in a good way. And if they became popular they would move to nearby Melrose Avenue.

Nowadays, sneaker culture and fashion mix with a new generation of skateboarders and Supreme collectors that make the block buzz. And even though Odd Future’s Fairfax pop-up store wasn’t the first black business on the block, Tyler, the Creator’s presence hyped up the block even more. Decades previously Lenny Kravitz and Slash both walked those same blocks, but they didn’t influence it the way Tyler has.

It’s the present of the black community that means just as much to me as our rich history.