The ‘death of the lesbian bar’ inspired the local roving pop-up parties that are keeping the scene alive.

No one in West Hollywood walking down Santa Monica Boulevard on a Saturday night would think Los Angeles is a city starving for queer nightlife. In fact, the doors are open at Fubar and The Abbey any night of the week; or if you’re in Silver Lake or further east, you can pop into Akbar or Redline. Though each location has its own vibe, even a casual observer can recognize a trend — they’re primarily patronized by cisgender, gay men. For queer women, trans men and non-binary folk, finding a place to meet with people from the community requires a lot more insider knowledge.

When queer party connoisseur Christina Cola moved to Los Angeles from New York two years ago, she had to be introduced to a friend of a friend, another queer woman, before she could find the events where she might meet dating prospects and potential new friends. Advertised on Instagram, monthly LGBTQIA+ pop-up parties have created a social network through different bars and venues across L.A.

“You start following one, and more and more come to your attention,” Cola says. She quickly became a regular at Paradiso Divine, a party for all “queer girls, femme, butch, trans and NB party people” that requires an RSVP to get on the guest list.

Though Cola doesn’t drink, the parties were a great place to have conversations and find people she had a lot in common with. It was the perfect entryway into a new city.

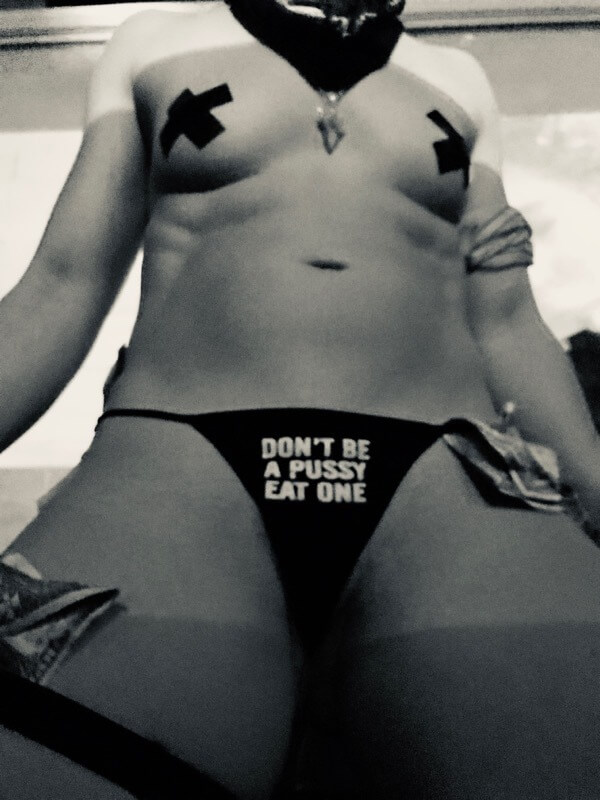

Mommy Issues is a “femme-forward” gathering of queer folks creating a space for themselves in L.A. nightlife. Photos courtesy of Chingy.

The proliferation of parties like Paradiso Divine indicates a need for events that cater to queer people who don’t fall into the cis male demographic. But they can’t seem to find a home. The Abbey hosts Girl Bar every Wednesday night, and while the weekly women-centered party is usually bumping, it’s not exactly a prime spot.

Mommy Issues is a nascent party organized by women who have been working or enjoying the scene for years. It launched in March at the Faultline Bar in East Hollywood and was promoted as a “femme-forward” night by their social media maven, known to her followers as Chingy. Although they were nervous about starting a new party, co-organizer Kristin V. said she knew it was going to be a hit when a long-time ex asked her if she’d be there, not knowing she was one of the women behind it.

Chingy says that the event was a “raging success by lesbian standards,” but adds, “if we were white, gay men we probably would have considered this a failure.”

“There’s a tipping point with these things. If there’s enough people and it’s really fun, you want to be a part of it. And if it seems like there’s gonna be a line, you want to get ahead of the line.”

Kristin V., Mommy Issues co-organizer

This is because lesbians, in particular, have a (perhaps unfair) reputation for staying home and not dropping cash when they do go out. Kristin, says she is not a fan of the stereotype that women spend less money; saying it perpetuates the idea and makes the concept of a more broadly queer bar less appealing. The trick, she says, is to incentivize everyone down the chain, from bar owners to patrons, and make your party seem like it’s going to be successful from the start.

“There’s a tipping point with these things,” Kristin says. “If there’s enough people and it’s really fun, you want to be a part of it. And if it seems like there’s gonna be a line, you want to get ahead of the line.”

This has proven difficult to maintain; the “death of lesbian bars” has been well-documented in articles by Vice’s JD Samson and by L.A. artist Kaucyila Brooke in her project “The Boy Mechanic.” The “last lesbian bar” in Los Angeles, The Palms, closed in 2013. Even when it was open, Kristin says she remembers the venue was seen as a “tragic” place to end up late at night — the space wasn’t conducive to dancing and kept people isolated in booths.

For Chingy, the issue is definitely about economics, not interior design.

“I think a lot of people are afraid of lesbians and afraid [that] we’re not marketable and that’s why we don’t have bars anymore,” she says. “A lot of the time we don’t make as much money as affluent, gay men. Anyone who makes less money than affluent, gay men has less things targeted at them, because we’re seen as a less viable business.”

Danielle Venator has been working parties like Mommy Issues as a bootblack for years; she won the title of California State Bootblack in 2015, (then called Southern California Leather Bootblack) and sees bootblacking at queer parties as part of the title’s obligations. The leather and kink scene is often dominated by cis men, and her visibility encourages other types of kinky queers to get involved.

Cruise L.A. is a kink-centered party for women and trans folk that has been running since 2017. It’s organized by Vanessa Craig and Pony Lee at Eagle LA, a historic leather bar that has been around in various iterations since the late 1960s. Venator said she made something of a home at Cruise, but her services are asked for at more types of parties now. As a traveling bootblack, she has her own perspective on why pop-up parties work for her community.

“Many people come here, they move here from all parts of the country, they’re tourists, they come for pilot season, you name it,” Venator says. “It’s a lot like Paris because the city is so visited and there are so many tourists, it becomes an insider scene. You have to know someone, you have to be on the right Instagram, you have to know the Facebook groups to gain access to where these monthly parties are … I really believe it’s a way to sort out people who are just here for the week or just here for the month — unless people can vouch for them.”

Vanessa Craig and Pony Lee started Cruise L.A. in 2017 to provide a space for L.A.’s kinky women and trans folk to meet, mingle and do their thing. Photos courtesy of Cruise LA.

Venator mentions the saga of another kink party, Soft Leather Club, that recently became members only. The Instagram feed of the weekly event — which does not cater exclusively to queer people — chronicled the issues the party was having with “bros” showing up to gawk at the elaborate costumes and public spankings. This is an issue that any queer or kinky party with a considerable following will eventually face, according to Venator. Gay bars in West Hollywood are so well-known, it’s changed the clientele.

“It’s so consistent that bachelorette parties figured out to go there for fun,” she says. “If you have the hot straight girls, the hot straight boys are gonna come. So, the clientele is rather mixed on a Friday or Saturday night. Which is not a bad thing, but it kind of loses that awesomeness of a gay bar. Because all the tourists that are coming in, too. If you’re a smart guy and you want to pick up some girls, you’re gonna go to The Abbey. If you come into town, The Abbey is the famous gay bar, you’ll put it in your Uber.”

Parties that cycle through venues and dates for every get-together create a layer of protection that a popular bar can’t offer. There are always new parties on the rise while others die out, which Venator suggests is an aspect of Los Angeles promoter culture and not a fault of the queer community. Staying on top of what’s new and hot means staying involved. But that gets to another stereotype — that everyone settles down with a partner and stops partying. Cola admits she hasn’t been to a party for some time because she has a girlfriend now, though she plans to come back out to celebrate Pride.

“You have to know someone, you have to be on the right Instagram, you have to know the Facebook groups to gain access to where these monthly parties are … I really believe it’s a way to sort out people who are just here for the week or just here for the month — unless people can vouch for them.”

Danielle Venator, roving bootblack and Cruise LA regular

It would be easier to know she can just go to Akbar to find that community again, but when asked if there is any downside to having to log onto Instagram to find out where Pride is happening this year, Cola says, “the main negative is running into your ex or past hookups.”

The possibility of running into past lovers haunts queer parties as it seems like a lot of the same people attend them. Yet, from Craig and Lee’s perspective, there’s also no anxiety about competing for attention.

In an email, Craig writes, “I celebrate all the LGBTIA+ celebrations and I love to see everyone’s twist on things, especially those doing events outside of WeHo. I’m always learning and taking notes. I’m also super happy to see a number of other queer and kink parties pop up, especially so many QTIPOC-exclusive play parties that are creating their own space.”

Lee agrees. It’s not a sign of rising competition, it’s a sign of expansion.

“We are all for more opportunity for people to get together and for another generation to keep the parties going,” they write.

A pop-up party isn’t just an inventive way to handle the lack of dedicated space for queer identities; they’ve become a form of expression for all the nuance, creativity and desire that the acronym LGBTQIA+ is meant to cover. So, there’s always room for more.

As Venator says, “it’s like you have all these different flavors of ice cream. You can have this one week [and] this one the other week. I encourage people, whatever flavor you’re feeling, go for it. That’s the beauty of all this choice and variety — don’t just pick one.”