Dr. Ryan Carpenter, racetrack veterinarian to several of the most high profile trainers at Santa Anita, has some answers.

Santa Anita Park in Arcadia reopened for live racing on a recent weekend under cloudless skies, abundant sunshine and with much fanfare. The hallowed track had not hosted a live race on either of its surfaces since March 3, when Santa Anita closed its doors because of the unprecedented uptick in horse fatalities since the start of the 2018-2019 winter meet on December 26.

Races throughout the weekend went off without a hitch. It seemed that Santa Anita had finally moved on from the near-constant headlines surrounding the deaths of the 22 horses.

The revelry was short lived.

In the afternoon seven horses, including a five-year-old gelding named Arms Runner, bolted from the gate at the start of the Grade 3 $100,000 San Simeon Stakes.

To the disbelief and horror of many, Arms Runner fell to the ground after suffering what amounted to be a catastrophic injury. He was vanned off the track and euthanized.

A staggering 23 horses have been euthanized since the winter meet began. (Editor’s note: Since the time of this article’s original publication, horse fatalities have risen to more than 29).

In light of the track holding the 2019 Breeders’ Cup in November, and more races to come, Los Angeleno spoke to long-time veterinarian and equine surgeon, Dr. Ryan Carpenter, at Santa Anita to ask him about why so many horses keep dying at the Arcadia racetrack.

Walk us through your examination of a horse before it steps onto the track for training.

I’ll meet with the trainer and they’ll often have looked at the horses before I got there and pull out the ones that they’re concerned about.

I’ll bring the horses in front me and I’ll jog them down and back, watch their gait and see how they’re moving and then I’ll put my hands on them and feel their joints and tendons and ligaments and bones. I’ll feel for any heat, any swellings, any sensitivity to palpitations. I’ll flex the joint to see if they resist the flexion and then we’ll make notes as to what we’re seeing. Based on how they jog, how they look and their clinical exam then we’ll make recommendations.

Does your examination change on race day?

I don’t typically look at very many horses that are going to run. In a typical race horse’s schedule, they’re going to work out on the track at race speed the week before a race. I always look at them the day after they work. It’s uncommon that a horse would have a significant injury walking, jogging or galloping.

I like to look at them the day after they breeze [a horse workout with the rider] so I know exactly how they look. At that moment I can tell you I believe this horse is safe to run next week or not.

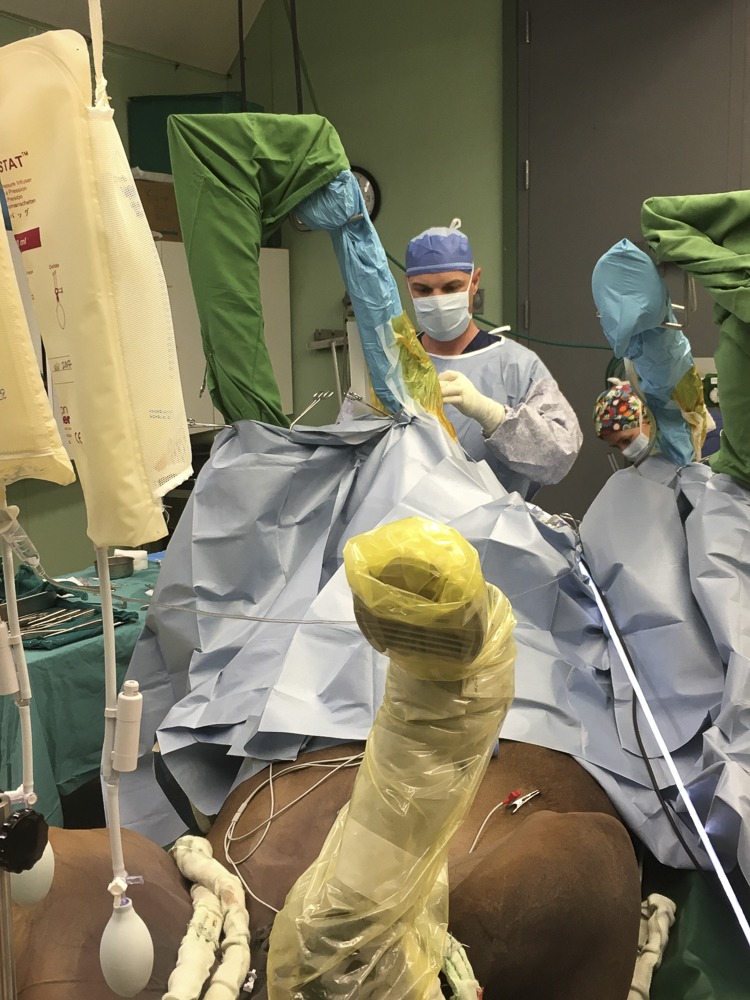

Dr. Ryan Carpenter performing surgery on a horse. Photos by Brandon Black.

Explain the use of furosemide (Lasix) in horse racing.

EIPH or exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage is a recognized disease. From a veterinarian standpoint, if I have a disease and I have a therapeutic medication to treat the disease, then it should be treated. A lot of people argue that they don’t use it in Europe on race day, which is true, but they train on Lasix.

I support the use of Lasix because it’s a therapeutic medication to treat a disease. We’ve allowed horses to be treated with Lasix for decades. If you look at some horses in Europe that are deemed “bad bleeders,” those horses will often get sold to the United States for a reduced price because they’re not of tremendous value in their world under their regulations. We take them on. We treat them. They can perform to an ability better than they could in their previous country. And then they’ve now entered into the genetic pool. So we’ve been breeding horses that are prone to bleed but are able to be managed therapeutically for a long time.

” I support the use of Lasix because it’s a therapeutic medication to treat a disease.”

Dr. Ryan Carpenter

Of the more than 20 horses who have died since the start of the racing season, many were 3 and 4 years old. What role does age play in the physical and mental development of a thoroughbred?

The reason why we saw three and four-year-olds [suffer life-ending injuries while on the track] is that two-year-olds weren’t on the track during that time period, but they are now. If you look at the injury database, you’ll see that the two-year-old age group has the lowest number of catastrophic fatalities compared to older horses.

Why so many three and four-year-olds [suffering catastrophic fatalities]? One, that’s the population of horses that are here. Two, it’s based on the industry. As a horse becomes a superstar, there comes a point where their value is better in the breeding shed than it is on the race track.

What about the physiology of a horse makes it difficult for veterinarians to mitigate fatalities in the sport?

What we know about injuries is that the vast majority of fractures are what we call fatigue injuries. When you look back at most necropsies or pathology reports from racehorses, what we see is a preexisting callus. What that means is that there was some damage in that area weeks preceding the break.

The hard part for us [veterinarians] is that we can’t always see that on x-rays. We put a bone scan here in the early ’90s and that was a game changer because what it does is show the biological activity at the bone. And in areas that we call “hot spots” or increased activity, we know that precedes fracture. The problem is that it’s great in some areas but doesn’t work very well in others.

The Stronach Group, which owns Santa Anita Park and several other racing and gaming entities nationwide, decided to propose to limit the dosage of Lasix a horse can receive at its two California-owned racetracks on race day from 5 cc’s to 10 cc’s, is this significant?

It doesn’t make sense to me to just arbitrarily cut it. The rule prior was that [horses] can receive between 3 cc’s and 10 cc’s of Lasix. The vast majority of horses, the standard dose, would be 5. There are horses that I treat in my practice that if you give them 8 cc’s of Lasix they don’t bleed. If you give them 5 cc’s of Lasix they’ll bleed a grade 1 out of 4 or a grade 2. [A grade is used to estimate the severity of EIPH on a scale of 0 to 4, with 4 being the most severe.]

For me, if I know that that 3 cc’s is the difference between seeing blood on an exam and not, to me there’s value in giving the horse the appropriate dose. The doses aren’t just dreamt up on a whim. They’re through a lot of science and research. That’s why we’ve come up with appropriate therapies.

If you look at different organizations like the Racing Medication and Testing Consortium (RMTC), which has been heavily involved in regulating medications in racing, a lot of changes that they’ve made in recent years have been made based on science and research.

Animal rights activists protest at the park. Photos courtesy of PETA.

The Stronach Group has also taken the step to propose a ban on the race-day administration of Lasix in horses born in 2018 and after, starting in 2020. Is this a step in the right direction for the sport?

This is where racing has really missed the boat. We need a national commissioner that oversees racing. You’ve got to create fairness in sporting events and the rules shouldn’t be different from state-to-state. There’s been a lot of push from the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) and different organizations to get uniformity. You shouldn’t be allowed to use medications in one state differently than another state.

“We need a national commissioner that oversees racing. You’ve got to create fairness in sporting events and the rules shouldn’t be different from state-to-state.”

Dr. Ryan Carpenter

Why is there such a big spike in horse fatalities this season compared to last seasons?

A lot of it has to do with the racetrack. What people don’t understand and sympathize [with] is that we’ve got to make a one-mile-long circle of dirt, consistent. We know in racing … that inconsistencies – changing from hard to soft to hard – are the areas where horses are prone to have fractures. There are dryer parts of the track and there are wetter spots of the track. Some parts of the track are completely in the shade and others are completely in the sun. When you have a surface that is a mile-long, is dirt, and dirt changes based on temperature, water content, air, that all plays a big role in maintaining the surface.

Because we’ve had so much consistent rain here, if you look back at the first two months of the year, the track was sealed or packed down tight for about 31 days of the first two months. The fact that it was hard as a rock one day, opened up to allow it to dry out and breathe and then sealed back in a couple of days, that’s just the definition of inconsistency.

A lot of earlier reporting on the surge in horse fatalities at Santa Anita put a spotlight on the conditions of the two surfaces at the track in light of the amount of rain received this winter. Despite the conditions of the track getting the all-clear on March 4 from Mick Peterson, we’ve seen several more fatalities since then. Is the quality of the track to blame for the surge in horses breaking down?

Yeah, I think the track played a big role in it. We’ve seen this problem at Del Mar when Del Mar put in its turf course (in 2016) and the turf course was really hard and we realized we had to aerate it differently. They had this problem in New York at Aqueduct during a really cold winter (21 horses died between November 30, 2011 and March 18, 2012).

The track surface plays a big role but you have to remind yourself that a lot of these injuries are fatigue injuries so they happen over weeks. It’s very plausible that you could have these microfractures take place for weeks, the track was deemed good, that horse could come back a week or two later when the track is good and have an injury. It’s not because the track that day wasn’t good it’s because the track last month wasn’t good.

As veterinarians, we’re looking for those horses that either raced or trained on sealed tracks, we’re trying to pull those at-risk individuals and do more diagnostics. You can’t blame all this on one thing.

The track surface plays a big role but you have to remind yourself that a lot of these injuries are fatigue injuries so they happen over weeks.

Dr. Ryan Carpenter

Has the sport arrived at its “watershed moment” (as described by the president of the Stronach Group, Belinda Stronach)?

I think it has for a couple of reasons. The first reason is we have not done a good job, as an industry, to talk about the good things that are going on in racing. There are a tremendous amount of horses that are having injuries repaired and coming back and running and doing great things. There are a lot of horses that are going off and having successful second careers. We’re not talking about all the surgeries we’re doing for free to give these horses a second career.

Right now, racing is being portrayed very negatively. People don’t even know that the good even exists. These horses at Santa Anita get the best healthcare on the planet. There’s an equine hospital, a lab, nuclear scintigraphy and there’s soon to be an MRI. It’s not uncommon for a horse to have sustained an injury or broken leg in the morning and have it repaired that afternoon.

What has been missing from the conversation about the string of fatalities at Santa Anita Park?

I think the thing that has been missing from the conversation is everybody getting in the room, together, and talking about how we’re going to do this as a team.

If you want to start talking about medication rules, let’s talk to the veterinarians and the organizations that out there. If you want to talk about whipping rules, let’s talk to the jockeys and ask them. Our whole common goal is to see fatalities decrease and see racing be successful. We all have a vested interest in seeing that happen.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.