Brenda Equihua is bringing Chicanx culture and style center-stage in a fashion world that still marginalizes the history of their impact.

Whether covered in images of tigers or the Virgin Mary, tossed onto a bed or spread ceremoniously over a couch, velvety soft San Marcos cobijas, or blankets, are a fixture in many Chicanx homes, evoking feelings of warmth and nostalgia. San Marcos blankets are so beloved they undoubtedly wouldn’t end up at a garage sale without cause. But if one ever did, L.A.-based designer Brenda Equihua would know how to transform it into a wearable work of art.

“I love yard sales and garage sales because you can learn so much about a person by looking at the shit that they’re trying to get rid of,” she says. “It’s so revealing. You’re holding a piece and it’s had these lives … What has this thing seen? What does it know?”

The candid 33-year-old Chicana designer and Franklin Village resident got her first taste of high-end fashion while uncovering second-hand pieces at tony neighborhood yard sales. Now, she’s made a name for herself with plush statement coats, jackets and hoodies made out of blankets inspired by the iconic San Marcos cobijas.

San Marcos cobijas are admired for their quirky designs and incredible warmth, but the production of the Mexican acrylic blankets ceased in 2004 when knock-offs from Asia, known as Koreanas, flooded the market. Since then, the original San Marcos have become collectibles and garnered a cult-like status along with countless look-alikes (which Equihua uses for her designs), internet memes (think Homer Simpson wrapped up in a giant tiger cobija) and online tributes to what some call “the original Snuggie.”

Making a Statement

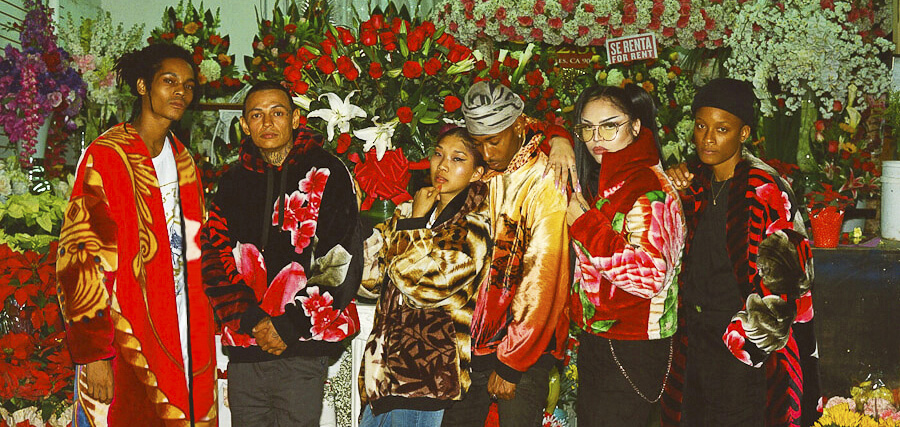

In Equihua’s recent “New Classics” collection, she combines the San Marcos cobija with outerwear designs, which have even gained attention by the likes of Vogue. Equihua says her Mexican heritage informs much of her design aesthetic.

“I kind of want these pieces to be like the alebrijes of clothes,” she says, referring to the fantastical Mexican folk art creatures conceived by the artist Pedro Linares. “I want my clothes to feel like this magical cloak.”

Covered in blooming red roses, vibrant tiger stripes or a praying Virgen de Guadalupe, Equihua’s pieces not only evoke the whimsy of this Mexican folk art tradition, but they have also become a stylish statement of cultural pride. Her oversize coats and jackets have appeared in ads geared toward young Latinxs like Dos Equis and Mercadorama’s co-branded “Mexico is the Shit” campaign and in a recent music video by reggaeton megastars Bad Bunny and J Balvin. An interview with Spanish-language TV network Telemundo earlier this summer put Equihua’s work on the map for a much broader Latinx audience, but she’s not one to let burgeoning success to go to her head.

“I kind of want these pieces to be like the alebrijes of clothes. I want my clothes to feel like this magical cloak.”

Brenda Equihua

“It is helpful and great to have these articles,” she says, “and I get excited, but I also am very careful about the level of excitement that I allow myself to have when things like this happen. Because I always want my work to be about my work, you know?”

Her Mom as a Style Icon

Equihua was raised in Santa Barbara, California by a single mom, who cleaned houses by day while attending beauty school by night. She gave birth to Equihua three days after crossing the border from Mexico — a legacy that imbues much of the designer’s work ethic and grit.

“It’s honestly been a driving force throughout my entire life,” she says. “When I was in school and when I was studying and when I was thinking about my life, I really thought about all her hardship — and how I really didn’t want all of her efforts and all of her pain to be in vain.”

Having grown up on Mexican cinema and folklore as well as obscure rituals like cutting her hair during the full moon, Equihua found few cultural references that resonated with her in her fashion design classes at New York’s Parsons School of Design — which she put herself through with a combination of odd jobs, scholarships, student loans and grassroots community fundraising. Marilyn Monroe and French designers such as Dior and Madeleine Vionnet were held up as style icons, but Equihua felt that way of teaching focused too much on high-end fashion with little regard for how minorities and people of color have influenced streetwear across the ages.

“There was never a mention about the Pachuco movement … like the zoot suiters,” she says. “We were always taught that fashion was top-down, and I never believed it.”

In many ways, Equihua’s style icon remains her mother, who would doll up her daughters’ faces with the latest makeup techniques from beauty school, decorate beautiful cascarones, hollow eggshells stuffed with confetti, to sell at Santa Barbara festivals and dress up in sequin gowns even for the most casual of parties.

“My mom was very into fashion,” Equihua says. “She just always had really great taste. She cared a lot about the way that she presented herself.”

“There was never a mention about the Pachuco movement … like the zoot suiters. We were always taught that fashion was top-down, and I never believed it.”

Brenda Equihua

Three years after her mother died, Equihua launched her eponymous fashion label to bring to life the designs she had long been storing in her self-described “closet of ideas” — now embodied by her micro design studio, packed full with finished coats and yet-to-be-transformed fuzzy materials.

“Whenever I’ve had to deal with a trauma, my creativity has been my number one thing that has gotten me to come out of that and to be able to make more sense of the world,” she says. “I run toward my creativity as fast as possible.”

Designing Clothes Within Reach

For Equihua, launching her own label meant a break from the high-end ready-to-wear and bridalwear she had been designing for brands like Tadashi Shoji and Monique Lhuillier. It was also an opportunity to make clothes within reach of the average person that could also speak to the Latinx community.

But even her first few collections failed to meet her own personal mandates.

“I was making these clothes that were beautiful, but it was so expensive,” she says. “I mean, at the time I was selling a shirt for like $1,000 and I’m like, ‘Who’s gonna save $1,000 for a shirt!?’ I crunched all the numbers of like how much does this person have to make to be able to afford my clothes. And I concluded that she would need to be making at least $500,000 a year.”

That was a wake-up call for Equihua, who says she grew up “relatively broke,” to rethink the clothes she was producing.

“It just felt like I was alienating all the groups of people that I really wanted to talk to and talk about through my work,” she says. “I realized after I launched [my first two collections] who was interested in them, like the people who had money and that were rich. And that’s cool … but I just wanted to be more accessible.”

With cobija coats, jackets, skirts and hoodies selling on her website between $350 and $700, she’s the first to acknowledge that her price points aren’t as accessible as fast fashion, off-the-rack wares, but she sees her designs as something to save for. And visitors to her online store can pay in installments.

But it would take another breakthrough for Equihua’s clothes to achieve the kind of reach she desired. After months of meditating on fashion during her morning L.A. Metro commutes —she’s called L.A. home for over 10 years and reluctantly drives a car now — an image fell into her head, influenced by the half-popped collars, askew shirts and slung-on sweaters swaying on riders in “cool” shapes.

“I saw a silhouette and a blanket,” she says. “I was like, ‘Oh my God!’ I just knew.”

Aside from telling her family, she kept the idea close to the chest. “If it’s not executed right, it’s going to become a meme,” she remembers thinking. In the end, she credits the L.A. Metro for originally planting the idea in her head — even if a coat made out of a blanket is a counterintuitive design to come out of sunny Los Angeles.

The Spirit of the Blanket

Equihua used scraps from previous pieces to create smaller items like fuzzy hoop earings and drawstring knapsacks. Photos courtesy of Brenda Equihua.

Even after learning that San Marcos blankets were no longer in production, Equihua says she remained committed to the idea because “the spirit of that blanket is still something that exists.” Instead, she turned to cobijas inspired by the brand for her material.

Equihua’s latest creations (all for under $160) include reversible hats, drawstring knapsacks, scrunchies and fuzzy hoop earrings she playfully calls “donas” (the Spanish word for donuts) made from meticulously saved leftover scraps from her cobija coats and jackets. It’s her way of giving them a second life.

“The voice of the fabric had changed,” she says, and so, she responded.

For Equihua, this is just the beginning of many more projects to come out of her burgeoning “closet of ideas.”

“This is just a fraction of the things that I want to do,” she says. “I mean, there’s things in there from my childhood … It’s kind of like a garage sale.”